Inspiration for blog posts can happen at the strangest, and most inopportune times, and this happened to me on Thursday last week, the penultimate day of preparation for the opening of Flinders Connect and a time when my mind was flying around the many last-minute jobs we still had to knock off. The inspiration didn’t so much hit me, it was more delivered in person as I was coming back with a quick bite of lunch, courtesy of Prof Colin Carati, the Director of the Flinders Uni Centre for Educational ICT. After exchanging pleasantries about the opening of Flinders Connect, Colin mentioned the blog post I wrote a couple of weeks back which in summary posited that the next big challenge for Universities could be how best to connect their students to large, open networks as a means to improve employability (based on research from the Booth School of Business).

Colin’s thought to me was a strikingly simple one – what if the real value of a MOOC is to act as a broker for students into these large, open networks?

I must do two things before I go any further.

Firstly, I must thank Colin for sharing that idea, and give him full credit as the inspiration for this post. I’ve no idea how long I would have stumbled around before twigging to this connection, if I ever did.

Secondly, I must apologise to Colin for the 30 seconds that I stood in his presence like a stunned mullet after he made the comment above – my mind was racing through the implications of his suggestion, and any sense from the words coming out of my mouth at that point were purely coincidental.

The story to date

At the time the MOOC wave hit, I was working for an edtech vendor, and it was an interesting time. More than one pundit predicted the sky would fall to various extents, but I can remember feeling that at the time nobody had yet worked out what the business model for a MOOC strategy would be, and that without a clear vision of where MOOCs fitted within a broader organisational strategy then the whole concept stood at risk of being another very large bubble waiting to burst. Fast forward to the end of 2013, and Sebastian Thrun’s admission that Udacity was a ‘lousy product‘ led to a predictable savaging from George Siemens, and as 2014 dawned some started to declare the whole MOOC movement as well and truly over.

I did at the time however suspect that the MOOCs that proliferated in 2012 were only a stepping stone to a then (and still) unknown future state, and I know I wasn’t alone in this thought. I also to this day wonder just how angry some of the ‘founding fathers’ of the modern MOOC movement (Cormier, Siemens, Downes, Couros etc) must be that their original connectivist-driven concept for a MOOC back in 2008 was hijacked and brute-forced into a dump-and-pump pedagogical model driven by a disruption agenda (read:venture capitalist ROI). Maybe I’m misreading the situation, but the MOOCs that got all the airplay in 2012 seemed a far cry from the cMOOC concepts that started it all.

But I digress.

Before wrapping up, it is useful to look at some of the potential answers to the question of why would a University embark on a MOOC strategy, and whether any of these in 2015 look like they have paid off.

Reason 1: To ‘hedge bets’ in the event of a large-scale disruption of the global Higher Ed market. To date, and perhaps we’re just too early on the curve, I’ve not heard of any mass closures of universities brought about by MOOC disruption. What has died down though is the number of bold predictions that were being made in 2012 that MOOCs were going to revolutionise, well, everything. That aside, should the ivory towers crumble, then those universities who were already partnered with ‘agile’, ‘progressive’ (read: venture capital ROI driven) MOOC providers might well be in a stronger position to survive compared to those who doggedly denied the possibility of a major collapse of the global higher education system. Time alone will tell on this one, but it hasn’t happened yet.

Reason 2: To educate the world! Yes, MOOCs were going to bring the highest quality education to the most far flung corners of the spherical globe in an altruistic utopia. Perhaps they have in some cases. The statistics (which are touched on in the Uni of Pennsylvania article) however indicate that most people studying a MOOC already have a university degree, and I’ve yet to see any evidence that MOOCs are transforming education in emerging countries (but please do share if you know something I don’t). Even with this in mind, MOOCs cost money to set up and run, so altruistic reasons alone are unlikely to be a sole driver, which brings us to…

Reason 3: To make money. From what I’ve seen, this can be done in one of two main ways. Firstly, it can be done directly (as in the EdX model) by providing the learning experience for free, but charging for certification. Secondly, it can be done indirectly by using the free MOOC course as an attractor for students who might enjoy the course so much that they consider studying a more formal (and fee paying) course at the offering university. Again, I’ve not seen any hard evidence that any university is going gangbusters on either of these fronts – and again, I’d love to know if any educational provider is actually making a profit from their MOOC strategy.

Reason 4: As an innovation skunkworks. This is probably the most valid reason in this in my opinion. Create a ‘special branch’ of a university that is detached from the core business, give it enough latitude to innovate outside of existing enterprise-wide technologies, processes and pedagogies, and see if anything comes out of it that could be applicable in a wider scale. Yet again, I’d love to know of any tangible and successful examples of this if they are out there.

The MOOC as a network broker – the fifth element?

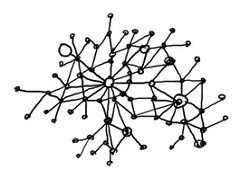

Now whether or not any of the above four drivers have been successful for universities in Australia and abroad, Colin’s comment made me wonder if a connectivism-based MOOC is the perfect enabler for a university to connect students to large, open networks, and in turn provide them with better employment prospects and more value from their university experience. Is this potential to broker networking opportunities the missing link, the enduring reason that universities might invest in a MOOC strategy? This was the lightbulb that went off in my head during that conversation, so thank you Colin for the inspiration.

Is this potential to broker networking opportunities the missing link, the enduring reason that universities might invest in a MOOC strategy?

You’ll note that I am only referring to cMOOCs here, not the kind of ‘watch a video, do a quiz’ MOOC that have been the focus of most of the media coverage and the darlings of Silicon Valley ed tech since 2011. I’ve got another post brewing on ‘dump and pump’ MOOCs after watching Mr11 attempt one last month, but that will have to wait.

As my mind rushed through the implication of Colin’s question, I thought about the current cMOOC I am participating in, Understanding Customer Experience. This has been my first crack at participating in a cMOOC, and it has been very different from the couple of ‘dump and pump’ MOOCS I’ve done in the past. As a cMOOC, it has a significant focus on peer interaction between students, who are a combination of fee-paying degree students and freeloaders like me who are along for the ride but without any assessment at the end. I wondered what Karlstad University’s strategy was for setting up the course like this, and now I wonder if my participation is primarily there to help their fee-paying students get connected to a broader network.

Am I the product in this free service?

In truth, it matters none to me. By connecting through this cMOOC I’ll benefit from the interactions with others more than I will from the content that is being shared by the university offering the course, most of which I could find on the interwebs if I knew what to look for. The only real loser in this scenario is anyone who is looking to make a truckload of money from any specific technology solution such as a MOOC-geared LMS platform or content management system. Heck, the UCE152 course doesn’t even use an LMS – it is all done through a WordPress site, personal blogs, YouTube, Twitter and the only expensive component I can see is the commercial virtual classroom tool, which could probably be swapped out for something like Google Hangouts if things got dire. The real value, for all parties involved, is in the connection and collaboration that occurs during the course – the technology is non-specific, and there is no big fanfare about the technologies used in the course to date.

Where to from here?

I’d love to hear if there are any institutions out there who have consciously looked at MOOCs as part of a network brokering strategy. Pretty much all of the discussions I see about universities embarking on a MOOC strategy relate to one of the first four drivers I listed above, and almost all of them still seem fixated on the value of the content and the qualification (which do, to be fair, represent the traditional value proposition for a student undertaking a university degree) rather than the value of the network which is created along the way.

I’d love to hear if there are any institutions out there who have consciously looked at MOOCs as part of a network brokering strategy. Pretty much all of the discussions I see about universities embarking on a MOOC strategy relate to one of the first four drivers I listed above, and almost all of them still seem fixated on the value of the content and the qualification (which do, to be fair, represent the traditional value proposition for a student undertaking a university degree) rather than the value of the network which is created along the way.

If there is life left in the MOOC, then perhaps it will be much closer to the original vision that Cormier & Co had than many might have thought possible back in the ‘peak of inflated expectations’ of 2012. A vision driven by connectivism not as an effective learning philosophy, but instead as a pathway to a far more tangible end result of students becoming part of large, open networks. To some, it may be sweet poetic justice that the concept of a cMOOC could ultimately outlive its shinier, more lightweight cousin – and I would be one of them.